I’m thrilled that Simone Hellier and John Thomson have recorded John’s setting of my poem Piano, along with the other four poems detailed in my previous blog. Here's a link to the recording on Soundcloud: https://on.soundcloud.com/kPeU53z1eqdMU3Fn9

The often-if-not-always great William Wordsworth had interesting, clear ideas about where poems came from and how they came to be written. He claimed that poetry was the spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling, whilst also arguing that it had its origins in emotion recollected in tranquillity, the idea being that the original feeling lies dormant in you whilst you distil its essence- or as it would be expressed today until you’ve processed it, the opportunity to compare human beings to computers rarely passed up these days. My poem Piano certainly did begin with a spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling, which was definitely recollected in tranquillity; in this case over a period of about four decades. Which, of course, could simply suggest a very lazy writer with a very ingenious excuse.

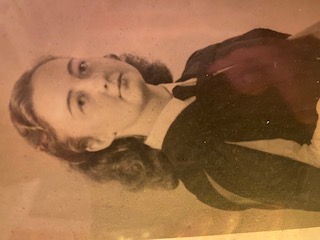

So, what about Piano? It’s dedicated to my mother, posthumously, I’m afraid- and I don’t know how she would have felt about the poem had she read it. She was a remarkably gifted woman- as a 1930s teenager she drew and painted with great skill, rural scenes and designs for fashionable clothing, as well as playing pieces of great technical difficulty on the piano.

At St Andrews, during the war, she read French and German, being additionally an excellent linguist, and this was the source of her romance with my father, a fellow Germanophile and music lover. Their courtship, which deserves a blog post, or novel, all of its own, is too intricate a tale for now, but one consequence of their marriage was my mother’s unfortunate separation from her beloved piano. The impoverished and itinerant lives of young academics was probably to blame, although my mother always claimed a less charitable reason, that my father had simply prohibited it, not wanting to have to listen to her practising. If that’s true he certainly relented, gifting her a beautiful Welmar piano one Christmas.

My memory of this is quite clear, as the poem describes- the snow outside, and my mother’s heroic attempts to rediscover in late middle age the youthful gifts she had in such abundance. The poem refers to her playing Fruhlingrauschen, an extremely popular piece of late Romantic piano music by little remembered Norwegian composer Christian Sinding; in English the title translates as The Rustle of Spring, and my mother always described it as her signature tune- her maiden name was Russell, and she loved the play on words. The piece is charming, Sinding evoking those rustles through sweeping arpeggios and a propulsive right hand theme; in its day it was hugely popular, an any collection of old sheet music in a charity shop will contain a copy.

In later life my mother was afflicted with dementia, resulting in her moving into a care home, where she spent the final years of her life, declining sadly and inevitably. On one of my last visits I found myself watching her hands, once so elegant and accomplished, now so lifeless; and thus was the poem born. I hope it’s a tribute to her, and that she would have liked it; and recognised the deep emotion that inspired it and that she was by then beyond feeling.

When she died, I was determined that Fruhlingrauschen should be part of the funeral ceremony, and tracking down a recording was almost impossible- the piece was written for and played by keen amateurs, not professionals. In the end I found only one- David Helfgott, a pianist whose career was blighted by schizoaffective disorder, and who was somewhat exploitatively celebrated in the 1996 film Shine. His recording echoed round Chesterfield Crematorium, and it was very moving; I hope the poem is too.

And here’s the poem…

Though the light outside burns harshly bright

Your blinds are drawn and all within’s as dusk,

Your hands upon the counterpane still as husks;

And I remember how one winter’s night

As snow drifted like lace against the whitened

Window pane, how you sat before your Christmas

Gift, its lid open, your hands spreading imagined airs

From its muted keys, eyes almost frightened

As round your feet lapped waltzes, polonaises,

Spilling from a case, clutched in your hands;

And later, as night fell across the Midlands,

Turning white to ashy grey, your fingers sung phrases

Which fell like snowflakes without end;

A girl playing Fruhlingrauschen for friends

Comments